A Bitcoin transaction is the fundamental action that transfers value on the Bitcoin network. In essence, a transaction is a piece of data that spends some amount of Bitcoin from one or more addresses and reassigns it to one or more new addresses. Every on-chain Bitcoin payment you send or receive is recorded as a transaction in the blockchain ledger. When Alice sends 1 BTC to Bob, what’s actually happening is that Alice is creating a transaction that references her existing unspent outputs (Bitcoin she owns from prior transactions) and assigns that value to a new output controlled by Bob’s address. This transaction is then broadcast to the Bitcoin network, verified by nodes/miners, and – once included in a block – becomes a permanent part of the blockchain.

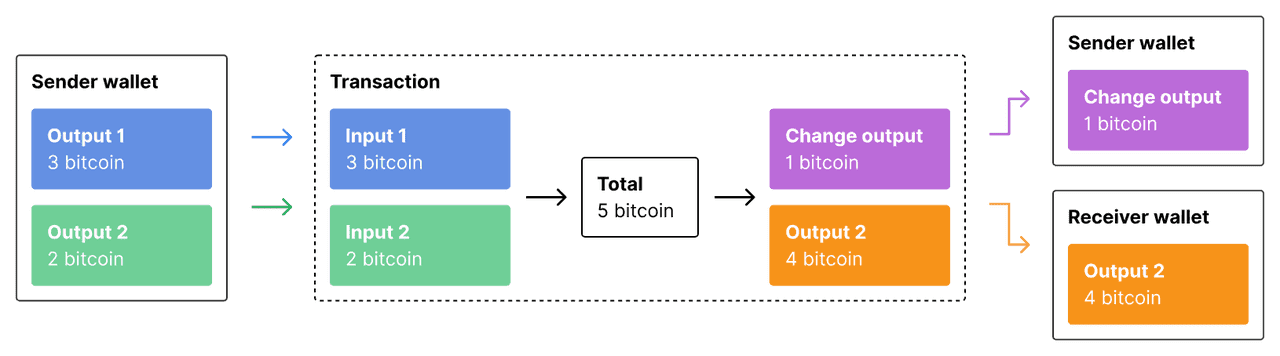

It may help to visualize a Bitcoin transaction not as moving physical coins from one account to another, but rather as updating records of ownership. Bitcoin uses the UTXO (Unspent Transaction Output) model. This means the ledger is a collection of outputs from past transactions that haven’t been spent yet (these are UTXOs, essentially “chunks” of Bitcoin controlled by someone). A transaction takes some of those UTXOs as inputs, marks them as spent, and creates new UTXOs as outputs destined for the recipient(s). Each output has an amount of BTC and a locking script (often represented by an address) that defines who can spend it next. Each input in a transaction must reference a previous output (by its transaction ID and output index) and provide a valid signature to unlock it. In simpler terms: inputs are the sources of funds, outputs are the destinations of funds. This design enables Bitcoin’s security and traceability: every unit of BTC can be traced back through a chain of transactions to its creation (the mining block reward).

When you use a Bitcoin wallet to send BTC, the wallet software typically will gather some of your UTXOs (for example, you might have two UTXOs worth 0.6 BTC and 0.5 BTC, and you want to send 0.7 BTC – the wallet will use those as inputs), sign the transaction with your private keys, and create outputs including the recipient’s address for 0.7 BTC and “change” back to your address for the remainder (0.4 BTC in this example, minus any fees). This entire package of data – inputs, outputs, signatures, and a few other fields – constitutes the Bitcoin transaction format.

Key properties of Bitcoin transactions include:

-

They are identified by a transaction ID (TXID), which is a hash of the transaction data. The TXID is like an identifier that can be used to look up the transaction on the blockchain.

-

Every transaction has a size (in bytes) and thus incurs a fee based on that size. Users attach transaction fees to incentivize miners to include their transaction in a block.

-

Transactions can have multiple inputs and outputs. Multiple inputs are often used when a wallet needs to combine several UTXOs to get the desired amount to spend. Multiple outputs can be used to pay several addresses in one transaction (e.g., paying two people at once) or, more commonly, to send one portion to the intended recipient and another portion back to yourself as change.

How Do Bitcoin Transactions Get Confirmed?

When you broadcast a Bitcoin transaction (which your wallet software does by spreading it to peer nodes), it enters the Bitcoin network’s “memory pool” (mempool). At this stage, the transaction is unconfirmed – it’s waiting for a miner to include it in a block. Full nodes independently validate the transaction’s authenticity: they check that all inputs correspond to UTXOs that exist and have not been spent yet, that the signatures are valid (proving the sender is authorized to spend those inputs), and that no other rules are broken (like the sum of inputs is >= sum of outputs, ensuring no coins are magically created). If the transaction passes validation, it sits in the mempool. If it’s invalid (say, trying to spend a UTXO that’s already been spent or not enough fee), nodes will reject it and it won’t propagate.

Miners then select transactions from the mempool to form a candidate block. Typically, miners prioritize transactions by fee rate (satoshis per byte of data) – higher-fee transactions are more likely to be picked first, since miners have limited block space and naturally want to maximize their earnings from fees. Once a miner successfully mines a block (by solving the proof-of-work puzzle), that block – containing a batch of transactions – is broadcast to the network. At this point, all transactions in that block are considered confirmed (1 confirmation). Each subsequent block added on top provides another confirmation, further cementing the transaction in history. After 6 confirmations, a transaction is generally considered irreversible for practical purposes due to the extremely low probability of a chain reorganization that deep.

Importantly, when a transaction is confirmed, its inputs (UTXOs) become spent and are no longer available for use. Its outputs become new UTXOs that can then serve as inputs to future transactions. This is how Bitcoin “coin ownership” moves forward: by transitively passing the right to spend outputs from one owner to the next through chained transactions.

Bitcoin Transaction Flow (source)

Transaction Fees and Speed

Every Bitcoin transaction carries a network fee, which the sender typically pays. The fee is equal to Input sum – Output sum (the difference between total BTC in and out). For example, if you spend inputs worth 1.0 BTC and your outputs total 0.998 BTC to various addresses, the remaining 0.002 BTC is the fee that goes to the miner. Fees are not fixed; they are set by senders based on current network conditions and how quickly they want the transaction confirmed. Because each block can only include around 1–2 MB of transactions (about 2,000–4,000 transactions on average, depending on size), Bitcoin’s throughput is limited, and users compete via fees during busy periods.

When the network is congested with many pending transactions, fees rise and low-fee transactions may experience delays. For instance, in periods of high demand, average confirmation times can stretch significantly. A dramatic example occurred in May 2023 and again in mid-July 2024 when surges in transaction volume caused backlogs. On July 19, 2024, the average Bitcoin confirmation time reached nearly 23 hours, with over 116,000 transactions stuck in the mempool, because many users were competing to get into blocks. Just a few days earlier, when demand was lower, average confirmation time was about 1 hour – illustrating how volatile network conditions can be. Typically, users monitor the fee market and set a fee that’s high enough to get confirmed within their desired timeframe. Modern wallets will often suggest an appropriate fee or have options for “economy” vs “high priority” fees.

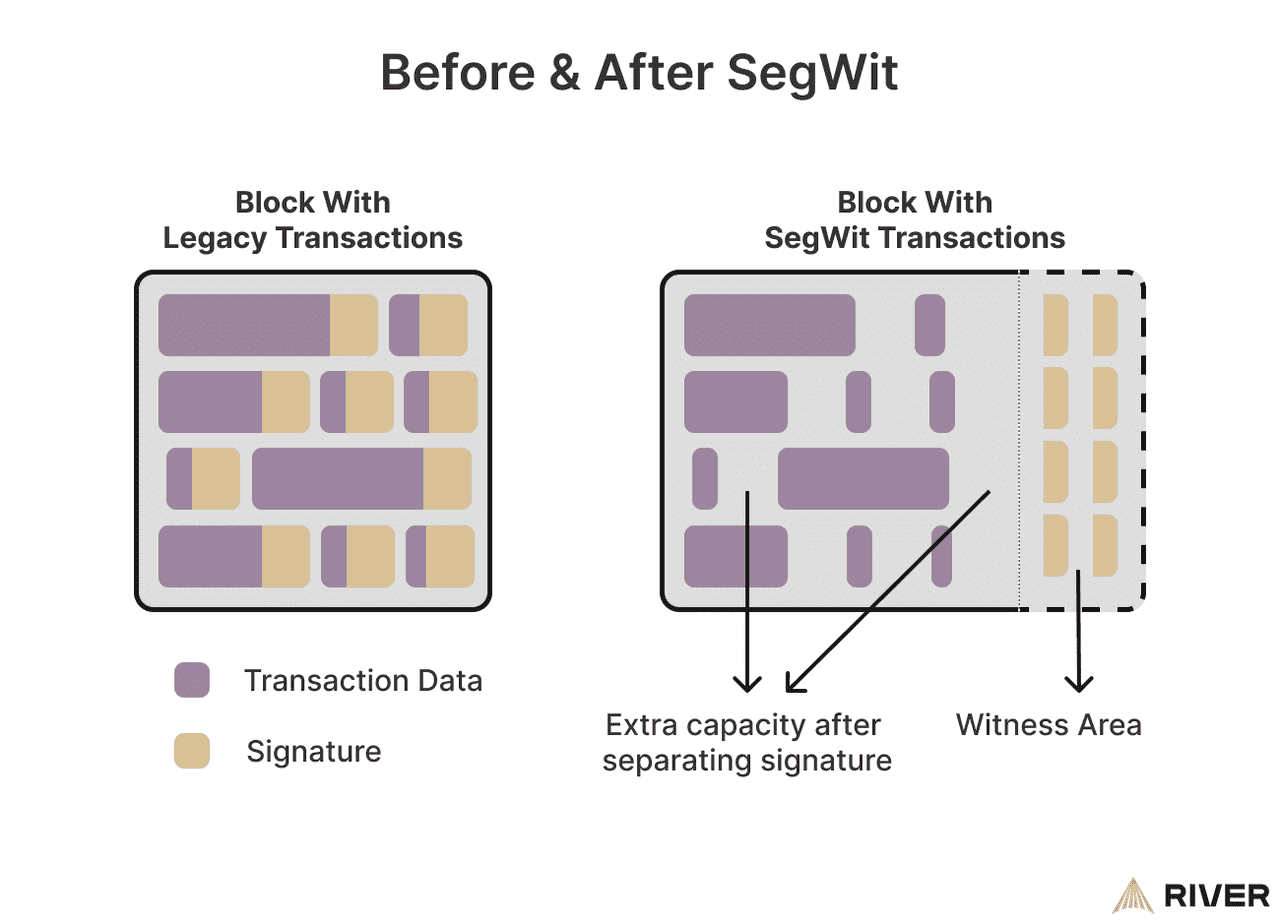

The fee per transaction also depends on its size in bytes, not just the amount being sent. A transaction with many inputs or complex scripts (like multi-signature) could be several hundred bytes and thus require a higher absolute fee to achieve the same feerate (sat/B) as a smaller transaction. Techniques like Segregated Witness (SegWit), adopted in 2017, effectively increased the block capacity and reduced the weight of certain data (signatures), allowing more transactions for the same 1 MB limit. Most transactions today use SegWit formats, which helps keep fees lower than they otherwise would be for the same demand. Another upgrade, Taproot (activated November 2021), further optimized certain types of transactions and smart contracts, although its impact on fee pressure is more indirect (by enabling advanced transactions with less data overhead for some use cases).

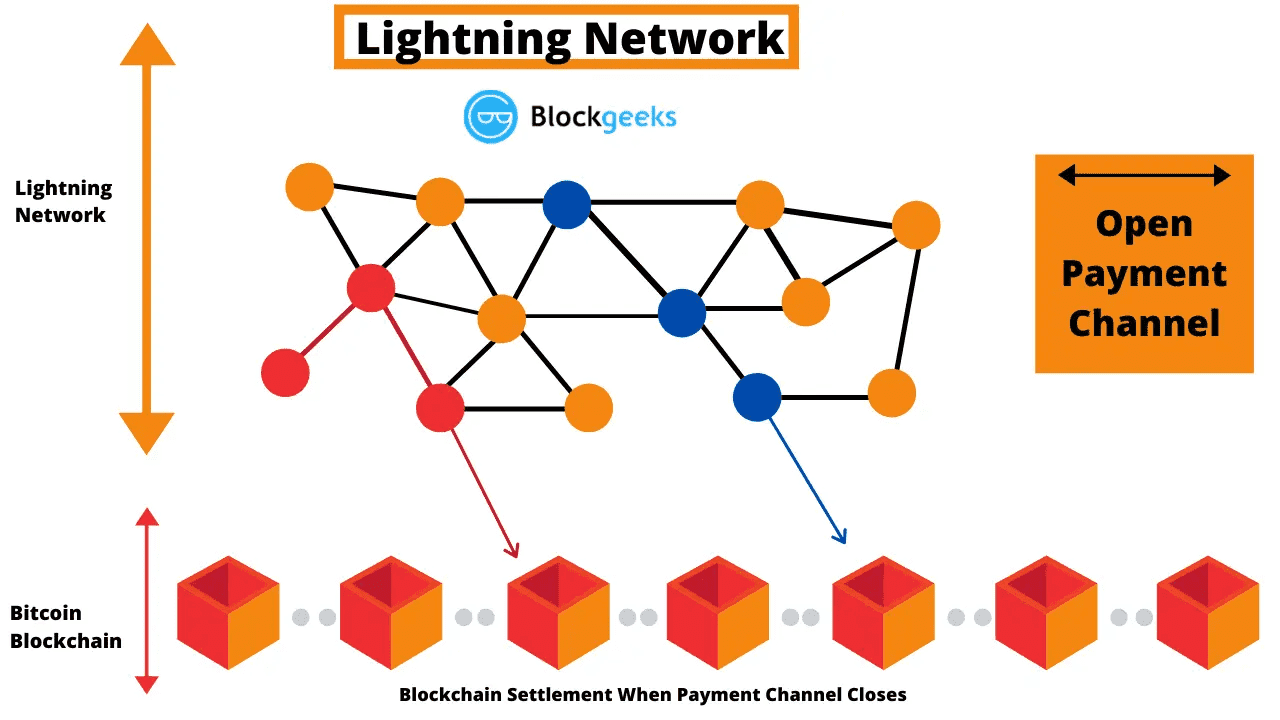

For users who need faster or more scalable transactions, Bitcoin supports layer-2 solutions. The most prominent is the Lightning Network, which allows users to open payment channels through on-chain transactions and then conduct many off-chain instant transactions between them (with final settlement on-chain when channels are closed). Lightning transactions are not on the blockchain and therefore can be near-instant and extremely low fee, making them suitable for small or rapid payments that on-chain fees or confirmation times would hamper. However, Lightning has its own use-case considerations and doesn’t eliminate the role of on-chain transactions – ultimately, opening and closing channels are on-chain events.

Lifecycle of a Bitcoin Transaction (Step-by-Step)

To summarize the journey of a typical Bitcoin transaction:

-

Creation: A user’s wallet constructs a transaction by selecting one or more of the user’s UTXOs as inputs (ensuring their combined value covers the amount to send plus fee). The wallet then defines outputs – usually one output for the recipient and, if needed, one output sending change back to the sender’s own address. Each output specifies an amount of BTC and is “locked” to a script corresponding to the destination address (commonly, a standard script that says only the private key holder of this address can spend this).

-

Signing: The wallet uses the private keys of the input addresses to create a digital signature for each input, placing that signature in the input’s scriptSig field (or witness field in SegWit). This signature proves that the sender owns those funds and authorizes their spending. If even one input is not correctly signed, the transaction will be invalid.

-

Broadcast: The signed transaction (a bundle of bytes typically serialized in hex format) is broadcast out to the Bitcoin peer-to-peer network. It propagates quickly to nodes around the world. Each node that receives it will perform validation checks (correct syntax, inputs exist and are unspent, signatures valid, etc.). If it passes, the node relays it onward and adds it to its own mempool of pending txns.

-

Mempool Waiting: The transaction sits in the global mempool soup with other transactions. It is pending at this stage. Wallets can show it as “unconfirmed”. It’s essentially waiting for a miner.

-

Mining & Confirmation: A miner picks the transaction up (if the fee is high enough relative to others, it likely gets priority) and includes it in a candidate block. When that block is mined (found the winning proof-of-work), the block is broadcast to the network. Nodes verify the block and then accept it, thereby accepting all the transactions in it. Now the transaction is confirmed and part of the blockchain at a certain block height. The outputs of the transaction are now spendable by their new owners (though most wallets will wait for one or more confirmations before considering the funds “safe” to re-spend).

-

Subsequent Confirmations: Each new block that arrives extends the chain. As blocks stack on top of the one containing the transaction, the confirmations count increases. This exponentially lowers the risk of your transaction being reversed (which would only happen if a block reorganization occurred, which is exceedingly rare beyond one or two blocks deep unless there’s a 51% attack). With Bitcoin’s block time ~10 minutes, typically within an hour (6 blocks) most exchanges or merchants consider the transaction final.

Bitcoin Lightning Network (source)

Special Cases and Recent Developments

While the above describes a standard Bitcoin transaction, there are a few special kinds worth noting:

-

Coinbase Transaction: Not to be confused with the Coinbase exchange, a coinbase transaction is the special first transaction in each block that creates new bitcoins (the block reward) and pays it to the miner. It has no inputs (since it’s “minting” new coins) and one or more outputs (the miner’s reward payout). Regular users don’t create coinbase transactions; only miners do as part of block creation.

-

Multisignature Transactions: Some outputs may require multiple signatures to spend (e.g., a 2-of-3 multisig address). These transactions, when spending, will have multiple signatures in the input corresponding to the multiple required keys. From a user perspective, this is just a more complex locking script on the output and a matching unlocking script on input. They are useful for shared accounts or added security.

-

Batching: It’s common (especially for exchanges or services) to batch payments by having one transaction with multiple outputs paying several people. This is more efficient than sending separate transactions, as it shares the overhead bytes across many outputs.

-

SegWit and Taproot outputs: Modern Bitcoin addresses (bech32 starting with bc1…) use SegWit, which moved the signature data outside the main block data into a “witness” structure, reducing fees. Taproot (a version of bech32 starting with bc1p…) allows more complex conditions like Schnorr signatures and MAST, but to the average user, spending these outputs still feels the same – just that the scripts and verification happen in an upgraded way under the hood.

A very notable recent phenomenon is the use of Bitcoin transactions for purposes beyond simple value transfer. In 2023, the Ordinals protocol emerged, allowing users to embed arbitrary data (like images or text, essentially NFTs called “inscriptions”) in transaction witness data. This led to a flurry of transactions used to mint and transfer these digital artifacts. The result was periods of extreme congestion and fee spikes on Bitcoin. Over the year, the average transaction fee reportedly soared by over 25× due to the popularity of Ordinals and BRC-20 tokens riding on Bitcoin’s blockchain. While this sparked debate in the community about whether such use cases are desirable, it showcased that Bitcoin transactions can carry more than just financial info – they can encode assets and information, leveraging the chain’s security. However, these trends also reminded everyone that Bitcoin’s base layer has limited throughput, and use cases that fill blocks (whether financial or not) will make transacting expensive for everyone. The network’s design is such that it prioritizes decentralization and security over high transaction throughput, hence why off-chain or layer-2 scaling like Lightning is considered the long-term path for handling everyday small transactions, reserving on-chain transactions for settlement and high-value transfers.

Bitcoin SegWit (source)

Tips for Using Bitcoin Transactions

For an average user, understanding some of these technical details can help in using Bitcoin more efficiently and safely:

-

Always back up your wallet, which essentially means backing up the private keys or seed phrase. Transactions are irreversible, so if your keys are lost or stolen, the Bitcoin could be gone permanently or spent without your consent.

-

Check fees before sending. During normal periods you might get a confirmation within 10–20 minutes with a low fee, but during peak demand (for example, when the meme token craze hit or an NFT drop is happening on Bitcoin), you might either need to pay a significantly higher fee or wait potentially hours/day for a low-fee transaction to confirm. Websites or wallet fee estimators can guide you on the current fee rates required for fast confirmation.

-

Use batching if you need to pay multiple addresses or consider using Lightning or other sidechains for frequent small transactions. This can save on fees and clutter on-chain.

-

Be aware that Bitcoin transactions are public. Anyone can look up a transaction by TXID on a block explorer and see the involved addresses and amounts. Bitcoin addresses are pseudonymous (not directly tied to identity), but the flow of funds can sometimes be analyzed. Techniques like CoinJoin or other mixing can improve privacy by making it hard to trace which outputs belong to whom.

-

If a transaction gets stuck (unconfirmed for a long time due to low fee), you can use features like Replace-By-Fee (RBF) if your wallet supports it, to bump the fee, or Child-Pays-For-Parent (CPFP) via sending a new transaction that pays a high fee and is chained to the stuck transaction’s output, incentivizing miners to include both. These are advanced fee management tactics.

-

Double-check addresses when sending. Bitcoin addresses are long strings of characters; modern wallets often have QR codes or copy-paste features. Always ensure the address you entered is correct (malware has been known to intercept clipboard data). Bitcoin transactions cannot be reversed, so if you send to the wrong address, there’s no recourse.

In conclusion, a Bitcoin transaction is the atomic operation that powers the Bitcoin economy – from the very first transaction where Satoshi Nakamoto sent 10 BTC to Hal Finney on January 12, 2009, up to the millions of transactions occurring today. It encapsulates a beautiful blend of cryptography (signatures proving ownership), distributed systems (propagating through a P2P network), and economic incentives (fees and confirmations via mining). Understanding how transactions work provides insight into why Bitcoin is secure and how it remains decentralized: no central party “approves” transactions – it’s the network of nodes and miners that enforce the rules and add your transaction to the global ledger, provided you follow the protocol. Every Bitcoin user, by creating and broadcasting transactions, participates in writing a new entry in this global ledger of value.